Is Climbing Legal or Banned in Cuba?

In January 2012 the Cuban authorities closed almost all access to the mountains in Western Cuba. The closure did not apply only to climbers, but all visitors, from cavers and mountain bikers to hikers and bird-watchers.

In Viñales National Park, access was technically limited to walking with official guides on the few trails “authorized” by officials for tourism long ago. The authorized trails reach very little of the Viñales Valley, and go nowhere near any of the climbing sites. The rest of this World Heritage site is technically off-limits to all visitors.

Years later, everyone has learned to live with the so-called closure. It’s a Cuban version of kabuki theater. The officials pretend that all access is closed and that no one is climbing, hiking, or biking in the park. Visitors hike, horseback ride, cave, or climb, unaware that violating an explicit closure. Ignorance is bliss.

Sometimes a ranger has happened upon folks climbing and politely ask them to move on. Two different climbers, however, put it in the identical words. “They don’t see you.”

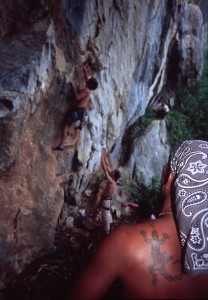

Climbing hasn’t stopped. New routes, even bolt replacements, are continuing in Viñales. Everyday climbers “sneak” through town heading to the crags draped with ropes, rack, packs, and helmets. Climbers report that they were able to climb everyday.

Venezuelan climber Xavier Garriga wrote that his group climbed at popular sites and even at Cueva Cabeza La Vaca, Guajiro Ecologico, La Costanera, and El Palenque, which are visible from much of the valley and town. Xavier concluded, “If you are thinking of traveling to Viñales to climb, you can go without problem. We invite you to go and climb everything you want!!!!”

No one has ever been cited. In fact no one has ever seen a copy of the closure order, and some doubt it ever was put to paper. So the scope, rationale, and penalties are unknown. Local officials themselves don’t say why the policy on access exist.

The best guess is that the closure was in response to Cuba’s obsessive and domineering state security. Foreigners walking around unsupervised in the mountains was the supposed problem. We recommend a knowledgeableCuban blogger’s attempt to make sense of what is going on.

Today, hikers and others enjoying the Viñales’ natural beauty outnumber climbers. Many others would be effected and kicking up a fuss if access were actually closed. The impact on the Viñales Valley and its almost 30,000 people could be crippling.

When Cuban and foreign climbers first began to explore the Valley in 1999, it was not a well-known World Heritage Site. Other tourists did visit, mostly on one-day tours. The routine was view the garishly painted, defaced wall called La Mural de la Prehistoria, walk through the paved, lighted, marred Cueva del Indio, and lunch at one of the thatched-roofed restaurants. If they stopped in town, it was to buy bottled water and post cards.

Probably just the style of eco-tourism desired by state security officials: distant views of nature, actual contact only at artificial or staged depictions, and no interactions with the ordinary Cubans of Viñales.

Viñales is now a completely different place. The town and trails are busy with visitors. Hundreds of Cuban families have turned their homes into small hostels and private restaurants to host the thousands of visitors who come to explore the Valley’s exceptional natural beauty and to walk among the valley’s traditional tobacco and coffee farms, where ox-drawn plows and horse-backed farmers still mark its agriculture. Individuals and groups come for climbing, hiking, birding, biking, and caving. Climbers stay for a week and more. There are museums, botanical gardens, cultural center, and live music every night. Everything is open, unsupervised, self-directed.

Climbing itself, however, has always been on shaky footing in Viñales. All sports education, facilities, and operations are conducted by the government. The focus is on those sports that are part of the Olympics, and Cuban athletes have won international competitions far out of proportion to the country’s size.

Individualistic sports that don’t harvest Olympic metals do not fit with its highly successful, but highly structured East German-Soviet sport model. The Cuban sport, tourism, and environmental authorities have taken no interest in climbing, nor any other outdoor recreation such as hiking, paragliding, and surfing.

Officials will say that these have not been authorized. Because the government controls almost all activities, officials often begin with the assumption that official authorization to do anything is required. At times a visiting climber has been told that a permit is required and will be available once climbing has been authorized.

Paradox, however, is the common state of affairs in Cuba. The lack of official authorization has not stopped the government from publicizing some of the Cuban climbers, promoting climbing in Viñales in the International Edition of Granma, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, and at one time, displaying photos of climbing in the new Visitor Center at the National Park.

Climbers have not faced any problems elsewhere in Cuba. At times the crux of the problem in Vinales appeared to be foreign visitors climbing with Cubans. In 2017, one of the leading Cubans was dragged in a neck-lock to the police station and accused of planning to climb with foreigners. They were in town. Carrying no climbing gear. In Cuba, however, you must prove your innocence. How do you prove that you were not going to climb later or the next day?

At other times, it was simply no climbing by Cubans. In Viñales, the government has told Cubans they faced imprisonment for climbing.

Since 2003, the government has been pondering whether it would “authorize” climbing, and perhaps until it is “authorized”, it is not considered an appropriate activity for Cubans. At least that is the generous explanation.

It is beyond us to explain why the government would permit foreigners to climb, but threaten Cubans with imprisonment if they climbed. When a climber directly confronted the officials for a justification, the explanation was, “foreigners eat ham and cheese, and you don’t and I don’t.”

The Cuban climbers are independent of the government and its sports apparatus. The government has not let the Cubans form any kind of organization. Their website was shut down as counter-revolutionary. It will not import climbing equipment for sale at any price.

Still, the Cuban climbers persist and grow. There are now Cubans climbing in most provinces. Every year there is an open-to-all festival and competition. The Cuban climbers receive assistance from the international access and conservation organization Access PanAm. They receive gear, bolts, drills, even climbing clothes from aboard. Without the pipeline of donated equipment, none of this can survive.

The Cuban climbers have taken this ambiguity in stride. Just another of the paradoxes they face every day.

Bottomline: Climbing is not a problem anywhere in Cuba except Viñales, where it is technically not allowed but goes ahead daily. When there are problems, it is only the Cuban climbers who are at risk. Even when Cubans have been arrested for climbing with foreigners, the foreign climbers have been permitted to keep climbing.