A Modern History of Climbing in Cuba

Cuba’s First Climber?

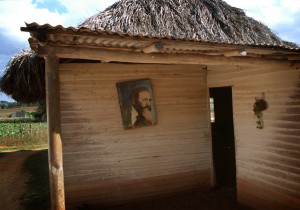

One year after Fidel Castro came down out of the Sierra Maestra mountains to claim triumph for his revolution, he declared, “The Revolution was the work of climbers and cavers.”

Did the icon and perpetual voice of the Cuban Revolution really mean to credit the success of his revolution to climbers and cavers? The context and source of this singular quote suggest that it is exactly what Fidel Castro meant.

The quote is from a two volume official history of the Sociedad Espeleológia de Cuba (Cuban Speleological Society). This massive history was written by Antonio Núñez Jiménez, Cuba’s celebrated naturalist and the author of over 50 scientific books. Although the Society’s paramount interest was caving, it had a long history of exploring all of Cuba’s natural environment, from caves to mountains and rivers. For example it organized the first exploration and descents of Cuba’s rivers (e.g., Toa) and early ascents of Pico Turquino (Cuba’s highest at 6,561 feet).

Núñez Jiménez was extraordinary in another way. He was a trusted colleague of Fidel Castro, and the framer of the Revolution’s agrarian reform, which seized and redistributed Cuba’s large ranches and sugar cane plantations.

At the Society’s 20th Anniversary, both Castro and Núñez Jiménez spoke. It was in 1960, just a year and a half after the triumph of the revolution, and it was the meticulous Núñez Jiménez who told the audience of Fidel’s quotation crediting the Revolution to climbers and cavers. Núñez Jiménez even added that Fidel said it to a journalist while they were together in one of Cuba’s abundant caves.

In his response, Fidel Castro lamented his frustrated desire to climb Pico Turquino, while fighting in the Sierra Maestra and staying one step ahead of the government’s troops. The revolutionaries had used the caves and mountains of Cuba as their bases and hiding spots. Although the oft-told story that the New York Yankees signed Castro as a pitcher is not true, he was known for hiking up the mountains in Oriente in his youth. It may not be far-fetched that Castro saw himself as a climber, even as he was fighting in the mountains of Cuba. In his speech at the anniversary, Fidel explained that Núñez Jiménez was motivated to climb peaks as a scientist, but that his own motivation to climb were those of an “alpinista”, an alpinist.

During the fighting of the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s, Fidel Castro may have been Cuba’s first climber. It was another 30 years before foreigner climbers began to visit Cuba. Had they known that bit of Cuba’s history, they might not have presumed that climbing in Cuba would begin with their visits.

The Mystery of the Españolas

The record of the first foreign climbers is murky and was discovered long after the fact. In 1999, when Craig Luebben, Cameron Cross, and Armando Menocal reached the top of the first pitch on the first ascent of the cathedral chamber of La Costanera, they were surprised to discover three rusty pitons, a loop of tied perlon, and a carabineer: an obvious onetime rappel anchor.

The record of the first foreign climbers is murky and was discovered long after the fact. In 1999, when Craig Luebben, Cameron Cross, and Armando Menocal reached the top of the first pitch on the first ascent of the cathedral chamber of La Costanera, they were surprised to discover three rusty pitons, a loop of tied perlon, and a carabineer: an obvious onetime rappel anchor.

Eventually a nearby campesino, a local farmer, told the Americans this story. About 15 years before he saw two Spanish women climb for a few days to reach that point on the wall. The campesino said the women climbers ascended no farther, although Luebben thought he saw pin scars on the next pitch. The first pitch had ascended a tree root for 50-feet, traversed dirty rock to a cave, and then exited onto a short 5.8 face to a ledge with the pitons. The Americans protected the exit and face with the widest crack gear then available, Big Bros; Luebben was the creator of Big Bros. On the descent, the Americans placed two bolts on the face, because they doubted that other climbers would carry ultra-wide gear to Cuba.

The story of the Spanish women climbers seems dubious. Albeit, to have climbed the first pitch, even without the wide-gear the Americans used, is plausible in terms of its moderate difficulty. It does mean, however, that these women came to Cuba equipped with pitons and hammers. It is also possible that there was an earlier generation of Cuban cavers who had pitons and ropes for caving and were making a first attempt at climbing. Perhaps the campesinosaw some long-haired climbers, heard them communicating in Spanish, and mistook them for Spanish women.

There is no denying, however, that the pitons were hammered in long ago by some climbers and they started climbing by tackling the longest, most intimidating, and elegant line that have been climbed to this day in Cuba. Although the identity of these first climbers remains a mystery, the central, arched chamber of La Costanera is named in their honor, La Bóveda de Las Españolas, “The Celestial Vault of the Spanish Women.”

The Early Cuban Climbers

The next developments are better known. The initial effort at modern climbing were by cavers, mostly by a particular group of them in Havana that called themselves the Arne Sakknussem section of the Cuban Speleological Society. Slowly the small group of Cubans in Havana taught themselves to climb, using their caving skills and meager caving gear.

The beginning approach to climbing fit their equipment and caving experience: drop in from above, drill an anchor, and then toprope the route; the hangers were removed for reuse. A few of the them were particularly anxious to move beyond the caving approach. These climbers were to become the first generation of Cuban climbers: Vitalio (Vity) Echazábal, Jorge Mederos, and Aníbal Fernández, who was only 11 when he started, but already caving and active in outdoor exploration with others in the Speleological Society of Cuba. Aníbal said that “people actually cringed when he, by then a veteran at 13, asked about the possibility of climbing in Cuba. “The whole idea seemed absurd,” he said, but “I was enough of a rebel to push forward and ignore the naysayers.” He cut the seat belts from his dad’s Russian Lada for a harness and bought some muddy ropes from other cavers. For instruction, they had a Petzl catalog.

By the time foreigners arrived with real gear, Aníbal and his recruits were toproping and using caving bolts, pitons and homemade chocks to lead their first routes. With limited knowledge and equipment and no experience, the scrappy Cubans managed to establish a few toprope routes at Jaruco, limestone cliffs about one-hour bus ride east of Havana. More lasting, however, was the training ground the Cubans pioneerioned at the incut limestone walls of the Castillo de los Tres Reyes del Morro, the Castle of the Three Holy Kings. Just called El Morro, the massive seaside fortress, is the signature landmark that has guarded the entrance to Havana’s harbor for four centuries — and only ten minutes from central Havana.

Around 1997, the Arne Sakknussem group staged a toproped climbing competition in the heartland of Cuba’s limestone cliffs, the Viñales Valley. By then, the core of the Havana climbers were Echazábal, Fernández, Mederos, along with Carlos Pinelo and Ananay Jiménez, who had won the women’s category in the climbing comp held in Viñales. However, the Cubans surprised themselves by the size of the turnout of cavers-turned-climbers. They were being to imagine that climbing could be a reality in their own country.

Later in 1997, Alberto Morales, a sports official from Colombia, who was also a climber, attended a conference in Cuba. He brought a rack of stoppers and hexes. The Cubans took Morales to the Viñales Valley. Morales and two of the Cubans (Echazábal and a Robertico, also from Havana) put up the first route there, a trad 3-pitch route they called Colombia y El Caiman del Caribe. (Colombia and the “Crocodile of the Caribbean”, a nickname for Cuba). (120M, 5.10 / 5+ – 6). Importantly, Morales left Echazábal his rack.

Cuba’s Wyoming Connection

The next foreign catalyst was to launch the eruption of climbing that continues today. It also was to continue and establish for a decade the tradition of donations by foreigner climbers that sustained and eventually installed the Cuban climbers as the leaders in new route exploration on their own land, a unique situation for most third-world climbing destinations.

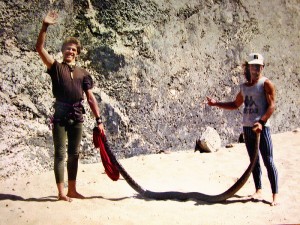

In 1997 and 1998, two Americans with climbing roots in Wyoming, USA, were to separately visit the Viñales Valley in Western Cuba in search of new potential climbing regions, recognize the opportunities of its sculpted limestone walls and vaults, and join together in the first real exploration of the valley.

Skip Harper from Colorado, who had climbed extensively at Vedauwoo and the Snowy Range, both in Southeastern Wyoming, and pioneered climbing in other Caribbean islands, came to Cuba alone, because as he said, “no one else would make the trip.” The U.S. travel restrictions on Americans required that he come in through the “back door” on an old DC-3 that had “no copilot and you could see outside through holes left where some rivets had fallen out.” Harper was “stunned to find a nearly uninhabited tropical paradise. . . and yes, there was climbing potential far beyond earlier descriptions.”

In 1998, Armando Menocal, was a long time climbing activist and Exum Mountain Guide from the Teton Range, in Wyoming, who returned to Cuba after a 40 year absence. Menocal’s mother was born and raised in Cuba, and on his father’s side, his great-grandmother’s cousins included a former president, Mario Menocal García, and Cuba’s famous classical painter, Armando Menocal, his namesake. Menocal said he “returned to find my family roots — and to check out a mountain region, Viñales, that my Lonely Planet guidebook described as a “miniature Yosemite, with the most spectacular scenery in all Cuba.’” As a long-time Yosemite climber, Menocal doubted that possibility, but could not resist going there. It was no Yosemite, but instead, in his own words, he found,

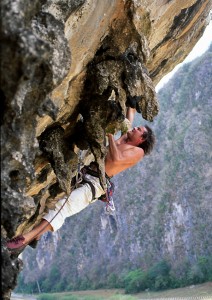

“A World Heritage Site that was a vast treasure of virgin rock. In the early morning mist, Viñales’ 1,000-foot, overhanging limestone walls, bulging with tufas and hung with stalactites, rose above the lush greens of palms and pines, and tobacco and coffee fields. A ballsy prospect dawned on me: Would it be possible to climb this unique architecture, through roofs, link alcoves, reach higher, bigger grottos, and in that way climb these overhanging caverns. Hooked, I was to return four times that first year alone, unable to sate my appetite for these sculpted three-dimensional walls.”

Menocal returned to Cuba two months later, in February, 1999, with a team of climbers from Colorado: Skip Harper, writer-photographer Craig Luebben, George Bracksieck, the founder of Rock and Ice magazine. Luebben and Menocal fell in love with Cuba’s virgin stone, and were to return to the Viñales Valley again and again.

From his first visit, Craig Luebben demonstrated an eye and ardor for the biggest walls of Viñales. Luebben pioneered walls and routes that, ten years later, remain Cuba’s longest, and perhaps finest routes. It earned him the apt nickname, “Mr. Mogote”.

Craig Luebben was tragically killed climbing in the Cascade range, Washington, USA, on August 9, 2009. Read the special, permanent tribute page to Mr. Mogote.

The Great Leap Forward

The first team of Americans, as Menocal put it, “wanted not just to explore climbing in Cuba, but to climb with Cubans. Had others attempted to climb these wildly overhanging walls? Were there climbers in Cuba?”

Ironically, a series of coincidences led them to the Cuban Speleological Society — the same organization before whom Fidel Castro had earlier made his “climbers and cavers” proclamation and that included the Havana climbers in the Arne Sakknussem group. The Society proposed that the Americans put on a climbing presentation and see who showed up.

It would not be an auspicious start. Luebben had recently completed a road tour in support of his just published climbing book. He volunteered to bring his slide show. The book was on ice climbing — in a country perhaps without a recorded sub-freezing temperature. The Americans arrived the day after the show was scheduled. It was in the afternoon at Havana’s sprawling Sports City campus. The broken window shades could not block the rays of the powerful tropical sun. Making out the images was almost impossible, but then, half the slides were on ice climbing anyway.

The dozen Cuban climbers who came did not mind. The shared passion for climbing was infectious. That afternoon the Cubans took the visitors to climb at their local crag, El Morro. Its 50 to 60 foot walls of immense limestone blocks towered above the sea and the castle’s sandy moats, providing ideal accessible climbing walls. The Cuban climbers shared the castle with sandlot baseball games, kids diving into the sea, and cavers practicing rappelling the walls and jumaring back up. Local photographers posed Cuban girls in evening dresses next to the sea to chronicle their quinceñeras, their 15th birthday and prelude to womanhood.

As Menocal realized, “We weren’t introducing the Cuban’s to climbing. They were showing us the resourceful, vibrant Cubans’ spirit.”

The next day the Cubans took them in a rural bus to their toprope area outside of Havana. Viva Cuba! the first bolted lead route was put up at Jaruco on February 12, 1999 (5.11b/6b+, FA Craig Luebben.).

Sport climbing in Cuba had started.

Two of the Havana climbers at that first Sports City slide show, Vity Echazábal and Carlos Pinelo, joined the Americans in a month-long, joint exploration of the length of Cuba.

Vity, the most talented natural climber, had mostly toproped but put up a couple of 5.7 or 5.8 routes in Jaruco with Aníbal Fernández. By the end of the trip, Vity was leading new 5.11/6c routes in Viñales. Vity was also the gear wonk, making nuts, hooks, and packs. His only equipment was a foot-peddle sewing machine. At times, two people would have to stand with all their weight on the peddle to pierce heavy material.

On the Americans last day in Viñales, they were joined by another young Cuban with short cropped blond hair. They did not know it at the time, but Aníbal Fernández had gone AWOL from the army and hitchhiked to Viñales to climb with the visiting Americans. After they dropped Aníbal in Havana, he went straight to the brig for two weeks. As he later explained, he was not going to miss the first genuine climbing experience, and he didn’t care what the army did to him.

Aníbal was to become Cuba’s strongest climber, and involved in every stage of the development of climbing in Cuba. He put up at least 200 routes. He explored the first areas looking for potential routes, introduced climbing techniques and gear into the country, and created relationships with foreign climbers that led to invitations to climb extensively in North America and Europe.

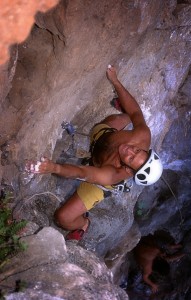

Aníbal may also have been Cuba’s first climbing celebrity when he appeared on a big, eye-catching poster advertising a brand of cigarettes. With his long blond hair hanging straight down from his near horizontal body, the dramatic photo revealed the wildly overhanging angle of rock climbing, Cuba-style. Flashy, beefcake, and hedonist, the poster was far from the norm in Cuba, where billboards, posters, even graffiti on the sides of building are restricted to socialist exhortation for productivity and sacrifice.

Aníbal may also have been Cuba’s first climbing celebrity when he appeared on a big, eye-catching poster advertising a brand of cigarettes. With his long blond hair hanging straight down from his near horizontal body, the dramatic photo revealed the wildly overhanging angle of rock climbing, Cuba-style. Flashy, beefcake, and hedonist, the poster was far from the norm in Cuba, where billboards, posters, even graffiti on the sides of building are restricted to socialist exhortation for productivity and sacrifice.

The Havana climbers seduced another strong and extremely committed climber. Abel Perez was a student of industrial design, who started climbing in spring of 2001, and bouldered throughout the summer. When school resumed in the fall, he found himself in class, thinking only about climbing. He dropped out, over the vehement objection of his father. Ardent, quiet, and focused, Abel discovered that he wanted only to climb, mostly new routes. “My father thinks that climbing is stupid. Cuba has no culture of climbing”, Abel explained. In time, he became the second Cuban to climb 5.13/8a.

The first routes done in Viñales were by Americans alone, but bringing along neophyte Cubans. From the beginning, the Americans brought gear to include the Cubans. This quickly developed into a full-fledged donation program supported by a dozen climbing companies that permitted the Cuban climbers to take the lead is exploring routes in their own country. In Cuba, route exploration and development necessitated power drills and bolts. One bolt and hanger, even if available for purchase, which they are not, would cost only slightly less than a month’s salary for a Cuban; an entire route, a years’ pay. A Bosch or Hilti drill could take a lifetime. Menocal brought a couple of used power drills for the Cubans to help them start putting up routes, and later Paul Laperrière, a Canadian, donated a new 36 volt Hilti.

Today the overwhelming majority of routes in Cuba have been put up by Cuban climbers. There may not be another a major climbing destination in the third world where that is the true.

The Early Years

Since the initial climbs in Viñales, it has been declared a U.N. World Heritage site because of its outstanding limestone landscape, traditional methods of agriculture that have survived unchanged for several centuries, and a rich colloquial culture reflected in its villages and its music. Viñales also has become a national park, and eco-tourism has taken hold. Climbing has become a central activity in the valley.

The first year of route exploration, 1999, has remained the touchstone. By its end, most of the largest faces on the valley’s mogotes had a least one route, and the longest lines had been climbed.

In the initial expedition of Americans and Havana climbers to Viñales, Craig Luebben did the dramatic classic Cuba Libre (3 pitches, 5.12a / 7a+) that was to be the quintessential Cuban route: cranking jugs and pockets in chiseled karst limestone on improbable lines winding through stunning overhangs of stalactites and tufa columns. Then, teaming with Cameron Cross, also of Colorado, Luebben, did the longest climbs in Cuba, the five pitch routes of Mr. Mogote (5.12a / 7a+) and Flyin’ Hyena (5.12b / 7b), the directisima up the center and through the very rim of La Bóveda de Las Españolas. Luebben and Cross finished off that season with a tour de force, an enchainment of the three routes in a day.

The next year, 2000, Luebben and Cross returned to add three more long, hard routes at La Costanera Wall, including the ultra-dubious Have a Cigar (5.12c-d / 7c), a you-have-to-see-it-to-believe-it climb.

David Ryan, another Exum Guide from Jackson, Wyoming, did several potential five-star routes. Colmillo Blanco (5.10b / 6a), done with Luebben, circles up a free standing tufa column. Filo de Cuchilla (5.10b / 6a) is a the knife edge on some of Cuba’s sharpest rock. And best of all, a route now known as Mucho Pumpito that may be the most overhanging 5.10 / 6a anywhere. Ryan linked a direct pitch to the second pitch of a Cross-Luebben route to create the “must-do” climb for every visiting climber.

2001 saw the Cubans taking the lead with Vity Echazábal and Aníbal Fernández putting up several long, difficult routes: Milenio, three pitches, and Huevos Verde con Jamon, two pitches, both 5.11c/6c+. In all, Echazábal and Fernández each added five routes, and Echazábal opened the Ancón Wall, with Alimentando Mosquitos (5.11+/6+). Ancón may someday contribute many classic tufa-stalactite link-up routes.

Also, in 2001, teams of Cubans and Americans returned to La Costanera Wall, which has yielded by far the most long routes in Cuba. Fernández and Ryan climbed the inside corner on the right side of the complete La Bóveda de Las Españolas (Chicken Run, 5.12a / 7a+, 4 pitches). Echazábal added Viernes 13 (5.11d / 7a, 4 pitches), on the outside corner of the cathedral.

Another joint team of Pinelo, Ryan, and Cuban-American Fernando Paulette, suffered through bat-scat, poison oak, and thorns on the wall that was to be aptly named Tormentos to establish the 3-pitch classic moderate, Guao, Guano, y Espina(5.10d/6b).

Several groups of visiting climbers of note also raised the standards of difficulty. Spaniard David Brasco put up an amazing 18 routes in May, 2001, developing the entire Guajiro Ecológico Wall, and the route that has become the test piece for the neophyte Cubans and most visiting climbers, Malanga Hasta La Muerte (5.12d-13a / 7c-c+).

Spring 2002 saw the arrival of a team of six talented Gritstone climbers who travel the world in search of perfect new routes. They included Neil Gresham, Tim Emmett, Seb Grieve, and Mikey Robertson. The Brits contributed perspective and Cuba’s hardest route to date, Emmett’s The One Inch Punch (5.14a / 8b+). In one month the team added many routes, including Gresham’s and Robertson’s Wasp Factory (5.12c / 7b), which has become another of the valley’s testpieces, against which climbers measure their likely success on Cuba’s cliffs. They climbed seven routes on the overhangs and stalactites of Cuba Libre Wall alone. Gresham invented a free start to Luebben-Cross’ implausibly acrobatic Have a Cigar (5.13b / 8a).

In time, the distinguishing characteristics of the mogotes of the Valle de Viñales may be their multi-pitch routes, linking vaulted chambers hung with imposing, sculpted stalactites and columns. There are more than two dozen of these classics, such as the routes on La Bóveda de Las Españolas, requiring endurance and technical descents with trail ropes to escape. These are big wall sport climbs.

In 2002, Aníbal Fernández teamed up with Dave Ryan for Dagas del Cielo (which the Cubans prefer to call Psycho Driller) 5.11c / 6c+, and with Luebben for Babalú Ayé (5.10d / 6b) on the barely explored Mogote de los Hoyos. Viñales’ first local product, Josué Millo, made his first contribution to these Cuba-classics with Cuenta con la Pelona (5.10d / 6b).

The Present

The pattern of the early years was that new route exploration would occur in periodic spurts when foreign and Havana climbers would come to Viñales. There they set up a “basecamp” of a dozen or more climbers for weeks at a time.

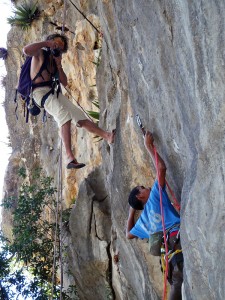

Two things brought that cycle to an end. First was the development of local Viñales climbers, who took over the lead among the Cuban climbers. These included Alberto Leivas, Reinel Sosa, and Yarobys Garcia. Yarobys was the first Cuban to on-sight 5.12d/7a. In his own quiet way, Leivas became the strongest climber that Cuba has produced. He was the first to climb 5.13/8a and then 5.14/8b+ when made the second ascent the hardest climb in Cuba, Emmett’s The One Inch Punch.

However, the first and by far most prolific of the home-grown Viñales climbers was Josué Millo. His tenure overlapped with Aníbal Fernández, and from 2002 through 2005 the two Cubans competed for the preponderance of first ascents and together totally dominated climbing in the valley.

However, the first and by far most prolific of the home-grown Viñales climbers was Josué Millo. His tenure overlapped with Aníbal Fernández, and from 2002 through 2005 the two Cubans competed for the preponderance of first ascents and together totally dominated climbing in the valley.

The second change was the emigration from Cuba of the first generation of Cuban climbers, the initial core of Havana climbers. Carlos Pinelo and Aníbal came to the U.S. for a rock guide course created for them by Exum Mountain Guides. Carlos dropped out of the guide course and defected. Aníbal took full advantage of the course, climbed both El Cap and Half Dome, and returned to Cuba in 2001. That same year, Vity Echazábal, Jorge Mederos, and Ananay Jiménez, on a training program to Spain, also chose to stay. Vity had once been caught trying to escape Cuba by sea. Abel Perez, the young student who had dropped out of school so he could put up routes, left Cuba in 2006.

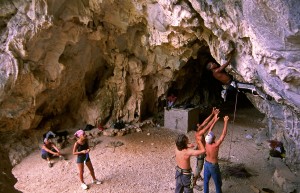

Cuban Loisbel Silvelio on his first attempt of “Malanga Hasta La Muerte” (12d/7c). It is a rare afternoon that someone is not attempting its fierce overhangs.

Finally, the last of that first generation of Cuban climbers, Aníbal Fernández, who had started climbing with little more than a catalog and a few stoppers and hexes, left in 2005. Two years later, Josué Millo, the first and most prolific of the home-grown Viñales climbers departed as well. Aníbal in Havana and Josué in Viñales, trained, mentored, and equipped the next generation of climbers by distributing donated gear. Their legacy may not be the measured in routes, but in the creation of the present community of Cuban climbers.

In Viñales, a new group of men and women were climbing almost daily. The newcomers included young, fit farmers, testing themselves on the valley’s harder climbs when not working in the fields. Most days one could find some of them training on Malanga Hasta La Muerte or nearby Wasp Factory, the benchmarks of skill and strength for the new climbers.

The unquestioned leader today is Yarobys Garcia, an exceptional climber, and committed to the challenge to do new routes and to the tradition of mentorship. Like Fernández and Millo before him, García has voluntarily accepted the role. In Cuba, with leadership comes responsibilities. Almost all donated gear sent for Cuban climbers has been passed through them, and they alone have been trusted to distribute the essential gear to neophytes and not horde or exploit it, as each of them could so easily have done. Also, Yarobys García has helped to create strong, independent groups of climbers in Viñales, and like Fernández before him, he has been an ambassador to Cubans in remote provinces, as climbing is spreading across the island. García has established a website on climbing in Cuba, escaladaencuba.com, which is probably the best source of information on new routes and especially new areas being explored outside of Viñales. It is difficult for those from other societies to appreciate how remarkable it is for an individual Cuban, outside of a state-run authority, to create and have a website.

The Future of Climbing for Cubans

As the first decade of climbing in Cuba draws to a close, the future of climbing for Cubans is in doubt.

Since 2003, Cuban climbers have been harassed by an officialdom that can’t decide whether it will “authorize” climbing, and pretends that until it does “authorize”, it isn’t an appropriate activity for Cubans. Foreigners, however, have been free to climb.

The era of the scrappy first generation of Havana climbers, such as Vity Echazábal and Jorge Mederos, drew to a close with the departure of their torchbearer, Aníbal Fernández. Aníbal had been run from Viñales and jailed for days. He felt forced to leave Cuba.

The remarkable next generation of Cubans, particularly the Viñales home-grown climbers, ended with the escape into exile of Josué Millo and Alberto Leivas. For years their leader, Josué, seemed to take his treatment by officials in stride. Josué’s entire family was persecuted. Each was a member of Cuba’s most oppressed splinter groups. His father had been jailed as a dissident (for failing to inform on the activities of a Cuban-American relative); his mother and sister were Jehovah’s Witnesses; and his brother was a homosexual.

In 2005, Cuban Security authorities banned Armando Menocal from Cuba. Menocal had been one of the first foreigners to climb in Cuba, published the Cuba Climbing guidebook and website, and, importantly, operated the program of sending donated gear that sustained the Cuban climbers and helped the Cubans to become an independent climbing community, free of government control or dependence, and the primary developers of climbing in Cuba. He remains permanently exiled by the government.

Finally, in 2009, Yarobys Garcia, the Cuban who took over as the leader in Viñales and has become the strongest climber, was arrested when climbing at the Cuba Libre Wall, taken to the police station, and then given an official notice by the police: climb again and face imprisonment. In Cuba’s legal parlance, this was the formal first step leading to the criminal charge of “peligrosidad” (dangerousness). Cuba’s criminal code permits anyone to be sentenced for up to four years in prison on the ground that the authorities believe that the individual has a “special proclivity” to commit crimes, even though he or she has not have actually committed a crime. The code broadly defines “dangerous” people as those who act in a manner that contradicts “socialist morality” or engage in “anti-social behavior.” According to human rights reports, the charge of “dangerousness” has targeted so-called ”anti-social” youths, most of them black, and 400 remain imprisoned. In Viñales the charge has been used in the last few years against gays, such as Josué’s brother.

For most, the addiction to climbing does not risk blacklist or prison. Nor does climbing force them into exile, separated not just from their crags, but families and country, and even forced to assume a new identity, that of an “exile”. But as those who climb in Cuba have learned, in some places, “commitment” must be redefined in those terms.